Theatre and the University

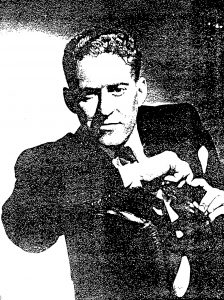

Des Connor, the Union Theatre's first Theatre Manager, tells the story of his long association with University theatre

Originally published in 1950

The Union Theatre is now twelve years old. As theatres go, it is, still a youngster. Those twelve years, however, have been rich in theatrical achievement; and as I have been with the theatre since its birth, and have shared in all of its fruitful adventures, those same twelve years have left me rich in memories.

My acquaintance with undergraduate theatre goes back before the opening of the Union. In the thirties, the annual University Revue was always presented in a down-town theatre. Trinity. College and the Teachers’ College also produced plays down-town. I was stage director in a number of these productions at the Palace, Princess, King’s, and Garrick.

In the mid 30’s, Revue was lavish, Ernest C. Rolls had introduced really large-scale revue to Melbourne audiences. It was 110 who brought to Australia the “showgirls’ walk” —–a hip-swinging, bust-slinging promenade which shows the female body off to the best. advantage. Tivoli show-girls still use it.

In that era of spectacular production, University revues were up with the leaders… In one show we got through 48 scene changes between eight o’clock and ten past eleven. That is still a record for swift-moving revue — professionally or otherwise.

First nights were stampeded. I was offered from £5 to £7 a seat, but unfortunately there were just no seats available, On their first-nights “Bridal and Bits” and “Getting the Bird,” both at His Majesty’s, stopped the traffic in Exhibition Street. University attendances were heavy, but we also had a big floating audience of down-town theatre-goers.

With the building of the Union, however, undergraduate theatre acquired a permanent home, When the old Garrick was pulled down in 1936, John Liston hit on the idea of giving all the equipment to the University, for a students’ theatre. A group of Varsity administrators got a scheme under way, and asked me to take charge. With Jimmy Guild, head mechanist at the Garrick, who had earlier been with Drury Lane for nine years, I had already talked over this scheme; but when the offer came, 1 declined. Run on amateur lines, the theatre would not have been able to maintain professional equipment and professional standards, The University people approached me again, suggesting this time that I run the theatre as a commercial proposition, allowing outside organizations to produce plays there. This would enable student productions to be put on at professional standards, without financial loss. I accepted, and called Jim Guild in to assist me. The Union is still the only commercially registered university theatre in the British Commonwealth.

Of the original equipment, there remain only the house curtain and the seats, on each of which you can still see. the letters “P.T.” —”Playhouse Theatre”, the old name for the Garrick. The original equipment was fairly adequate at the time, but as income from outside shows piled up, we were able to replace it and add to it. We installed a comprehensive switchboard, and first-rate sound equipment.

Financially, the first year saw us £8 down. After that the theatre paid its way, until depreciation began to catch up on us, three years ago. We lost £300 that year, but we may again have our head above water this year — thanks to some lucrative outside shows. The theatre has just been re-carpeted throughout.

We have since earned fame, both at home and overseas. The Union Theatre is perhaps better known in London and New York, than it is in Queensland. For that, we may thank the overseas celebrities who have trodden our boards. Some truly celebrated artists have come, have seen, and have been conquered — Percy Grainger, Baronova, Paul Friedman, Ted Shawn, Sir Bernard Ileinze, Sir Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, the Boyd Neel Orchestra, Ngaio Marsh and the Canterbury Players — these, and many more, have all appeared on the Union stage. Many other visiting artists have seen performances from the stalls, sometimes to seek talent, more often just to seek good theatre.

When Olivier spoke from the Union stage, he thought he noticed a fellow thespian watching him from the front row. Uneasily he turned to me. “Am I nuts?” he asked. “I swear I saw Chico Marx in the front row.” And so lie had! When I reassured him, he breathed a sigh of relief. “I thought it must have, been the behzedrine,” he muttered. Olivier, by the way, proved himself both actor and technician, and a thoroughly down-to-earth theatrical to boot. When I showed him over the theatre, he opened up a floor-well and said, with approval: “Plenty of circuits!

Of all the overseas artists who have been billed to appear at the Union, Ted Shawn, the American dancer, left the most lasting impression on me. I shall never forget a luncheon at Menzies, arranged to introduce Shawn to a group of locals. We had met earlier in the day, and I spoke to him on the assumption that he would remember me. “I suppose you will want a dress rehearsal today,” I said. He was to perform in the Union that night. “No,” he replied, in a far-away tone, “I can’t rehearse the day I have to dance. When I perform, I am with the gods, and to practise on the same day would be nothing short of sacrilege!” A pause and then: “You’re from the press, aren’t you?”. “No,” I answered, “I’m the director of the Union Theatre.” “My God,” said Shawn, lowering his voice. “How soon can we start? Boy, do I need some practice!

I can also remember Baronova very clearly. She was one of the most nervous people to appear on the Union stage possibly because Arnold Haskell was in the front row of the stalls, and ballet technique could be inspected at very close range in such a small theatre. But she had no need to worry. The audience paid £1 a seat. As they left, they paid another 5/. each for an autographed programme the whole 499 of them! They had seen some superb dancing.

Celebrities come and go; casual companies move into the theatre and out, paying for a few days’ run at a time but the undergraduate theatrical groups provide continuity. For them, the Union is not a casual stand, but a permanent home. It was built for them, and in them I hope its strength will lie. It was some time before undergraduates realized that they had a theatre, in the true sense, but the University’s own theatrical companies have since then built up some fine productions, and University actors have provided some great moments in the Union.

Bill Ryan’s “Hamlet” is now only a legend to all but a few undergraduates, but I can remember a couple of nights when Ryall reached great heights when his movement, appearance and voice brought splendid life to familiar lines. Unfortunately, many university productions have been hindered by an excessively literary approach. Too often the spoken word is the only part of the play that counts. Shakespeare was every man’s dramatist, capturing life from the sidewalks of London. He was a sort of Elizabethan Donovan Joyce! Too often, academic producers have polished dialogue to the exclusion of all but “Literary” values. They have wiped out all the blood-reds and yellows of the theatre. Ryan’s Hamlet was erratic; he threw polish to the winds, and achieved fine theatre. He captured the blazing colours.

“Anna Christie” was another “yellow and red” production. So, too, was “Oedipus,” in which a company from the Conservatorium did a very good job. Alan Money, in the title role, was superb. The one weakness of “Oedipus” was the failure of the choruses; they did not come up at all in production. But then how many Greek choruses do? There is a point at which literary appeal cannot be transferred to the stage not, at any rate, the box stage. For successful work, we need to understand and respect the present stage and its conventions.

It is interesting to note that there has been no good Shaw in the Union but no one can play Shaw well. He talks a great deal, but gets nowhere; there are too many words in his sentences, and too many syllables in his words. Certainly, he has proved to be a paying proposition, but Barnum had nothing on G.B.S.— he talks them in and he talks them out.

“St. Joan” was the only Shaw that. I have listened to with comfort. The M.U.D.C. presented a fine production, but there was more Max Nicholson than Shaw. The text was ingeniously cut, and the cast contained some beautiful voices. Nicholson had a magnificent ear for stage voices.

I am sometimes asked what has been the, best show in the Union, For atmosphere. and for hold on the audience, I would choose “Ghosts” or “They Came to a City.” “Ghosts” called for a mature cast. Young actors had to rely on make-up, movement, and voice, to give them age. In “Ghosts” they achieved this, and built up an authenticity which held the audience enthralled. “They Came to a City” was outstanding for its display of stage technique. The atmosphere was built up with 28 spots, which had to light up the individual characters as they spoke, and fade out as they ended their lines. It was also a well-written and well-produced play, with an unusual treatment of a quite well-known theme.

I was delighted to have “The Time of Your Life” on the Union stage. I like Saroyan — he has a philosophy which is fey and yet sincere, a philosophy which is derived from the sidewalk, and yet embodies a wistful and unperverted love of mankind. His plays are hard to do, especially for students. The characters are disjointed, elusive, deeply adult, yet superficially juvenile. The American idiom is also difficult. The Trinity production of “The Time of Your Life” achieved an authentic idiom where other productions have failed. The Queen’s production of “Winterset”, for instance, fell down in this respect. Although Bill Ryall, Meg Smith and Bill Scott turned in some good performances, the production lacked an authentic idiom.

The colleges have been a healthy influence in University theatre, In my opinion, there has not been a play written which could not be cast in the Cal. Unfortunately, the regular student groups tend to form cliques, and their work becomes stereotyped. The colleges, on the other hand, have to seek for potential actors among numbers of college students who have never acted before. Thus they have a constant turnover, and their casts are fluid. The team-work in college productions also excels anything to be found in the productions of the regular University theatrical groups.

Between them all, these various groups have provided some memorable theatrical experiences. Revue has also provided some brilliant entertainment, and of all Revue artists, perhaps none was greater than Fred McNaughton. He was a find. To build up his acts, he wrote music and lyrics, and then produced and rehearsed original dance routines. He was an individualist — the acts were his, and his alone. A natural “dumb comic,” he delivered the goods unaided and even unsolicited, at first.

One morning he came into me and said: “I’ve got a song.” I told him to see Terence Crisp, who was producing; but he insisted on trying out the number there and then. Taking off his coat and shirt, he revealed a red and white football guernsey underneath. From at pocket of his coat lie took out a battered sailor’s cap. Then, with an audience of two or three cleaners, several technicians and myself, he sang his famous first song, “Swimming Under Water with the Lord Mayor’s Daughter.”

There is no need to tell the rest of the story. McNaughton was a sensation in three Revues before the war. He was killed early in the war. He was a quiet lad, but his performance was always spontaneous, generally crazy, and never the same twice. He was a brilliant improviser, but he knew when to stop. Only once did he over-tax my patience. As his fame increased, he developed an ambition to do a ballet turn on a stage under three or four inches of pin.feathers. One day he walked into the theatre, opened a huge sack, and emptied a load of these feathers in the centre of the stage. We chased them for weeks.

Revue has seldom failed to produce some outstanding moments. Who could forget, for example, Keith Macartney singing “I’m a tree”? Or Joy Youlden’s “Row, Row, Row.”

In addition to the student dramatic companies, the technicians of the University Theatre Guild have played a vital role in the development of the Union, which has been a laboratory for technicians as well as actors and producers. The Union technicians began with the theatre. A group of engineering students, eager to work in the theatre as a hobby, attached themselves to us, and proved a source of strength. At first they were quite unpaid, but in 1943, when the theatre was on a sound financial footing, they came to be paid out-of-pocket expenses. Students who were keen to live in the theatre gained valuable concrete experience from their work with the Theatre Guild — two of them are now working in London theatres, two in New York, and one in Paris.

Our sets have been designed neither to dominate the actor, nor to take attention away from the play. Simplicity is essential. Scenery should be designed in such a practical manner that an actor can make complete use of his set. To some producers the set is untouchable, whereas it should be regarded as part and parcel of the actor’s equipment.

It is essential that set-designers should have a sound knowledge of stage-craft and theatrical mechanics before attempting to put pencil or brush to paper. Admittedly, it is difficult for people to get into theatres and learn from the inside. Too many artists, however, are misled by arty-crafty books with flamboyant pictures of unmanageable sets. A set is built of timber, canvas and electricity.

Light is the stage-designer’s finest paint-brush. In most cases in both professional and amateur theatre, producers and designers like to let their audience see everything. I don’t. Atmosphere counts for more than detail — too much detail is overpowering and loses the actors, as we lost the actors in “Edward II”.

The Union Theatre is handicapped because it has a shallow stage, but we have used light to conquer it. Light is increasingly becoming the most important medium between actor and audience. Melbourne’s professional theatre has failed to realize this. A leading down-town theatre has one of the finest switchboards in the world; unfortunately, it is not being used for what it was intended.

When I came to the Union in 1938, all I wanted to do was to start .a University theatre where experiment could be presented, with accent on light and design, Looking back, the achievement has been fair enough. Where in the British Commonwealth has another theatre of the kind been developed in twelve years? Brett Randall’s Lillie Theatre has done outstanding work in Australia, but otherwise the repertory movement has remained much as it was.

The Union Board and the Union Finance Committee have given me the utmost assistance in financial matters. With this assistance, the Union Theatre has done some splendid pioneering. We have staged the first Intervarsity drama festival in Australia, and have organized Australia’s first international Film Festival. Always remember, however, that the Union is the students’ theatre. It has, I hope, given the University student an appreciation of theatre art, during a period when most Australian theatre-goers have been all too ignorant of that art.

For the future, I hope that members of the University community appreciate and encourage the dramatic efforts of undergraduates. Let us continue to develop a University united and passionate in its love of good, imaginative theatre.