Interview with Suzanne Ingleton

Suzanne discusses her time in student theatre during the 1960s including her involvement in the Architecture Revue.

Originally published in 1990

Transcription: Interview with Suzanne Ingleton

Now tell me firstly, what years were you at Melbourne University?

Alright, well, I began in 1962, so I was in the Class of ‘62 at the Architecture faculty, I joined the Architecture faculty. I came straight from matriculating at Lauriston Girls’ School and I wanted to do Architecture, just as a romantic idea that it would be something exciting to do at University, which is where I wanted to go, but I just didn’t want to do Arts which was what everyone else was doing, and I certainly didn’t want to do Medicine.

I remember my headmistress once saying to me that, because I had no maths, I could do Interior Design and marry an architect! Which is strange for a woman who was quite a feminist, Gladys Davies, but yeah, she did say that to me, mainly because I hadn’t done mathematics. I sort of scooped up maths in the last year and didn’t sit the exams, still didn’t understand a thing. I still don’t, and I went to Uni to do Architecture, not even knowing what the Faculty represented at the time. It was the most glamorous, seductive Faculty and everyone just loved us! For we were the trend setters, the style setters, we were the anarchists. We weren’t quite as bad as the Engineering faculty but we were always much more attractive and much cleverer, you know, and all the boys drove extraordinary cars: French 2CV’s, old Volkswagens and stuff that was really far out. We wore jeans — no one else wore jeans in the University.

It was the most glamorous, seductive Faculty and everyone just loved us! For we were the trend setters, the style setters, we were the anarchists.

But you completed your Architecture Degree didn’t you?

I did, yes. I finished University in 1966 which was my fifth year and then I had to make up some practical time, cos you needed a year’s practical experience before you graduated and so I graduated in 1967.

So, had you had any background in theatre before that?

I’d done theatre at school. I mean, theatre was where my passion was, and one suppressed that slightly, back in the sixties, because there wasn’t a future in it. There was really no Australian theatre. The only theatre that happened usually came from overseas, and it was only during the early sixties that people like the Emerald Hill Theatre got going – Wal Cherry was down there. Melbourne Theatre Company kicked on a bit in the sixties after being a sort of playground for English actors, I think. It was a strange time. But I happened to be at Melbourne University, and I walked into the Architecture Faculty and discovered they had this thing called the Architecture Revue, which I had never heard of.

Was that in the first year?

Yes, my first year. I sort of went in and everyone sort of said to all the first years, ‘you’ve got to be in the Revue, you’ve got to be in the Revue’ and I’m going ‘yeah, yeah, what’s the Revue?’. So I’d hooked up with Penny Brown by then. She and I were best friends all through that and all through those years and still are, and we just started to devise scripts and stuff for the revue.

So this was in your first year, ‘62?

Yeah, ‘62. In 1965 I co-directed the Revue with Darryl Wardle and in 1966 I directed the Revue. I think I was still the only woman to have actually done that, I don’t know, and I also won the thesis prize that year, so there you go! [laughter]

Now tell me about the content of the Architecture Revue?

Content involved being very clever with words and making up scripts. If you devised a script you’d get on the stage. If you were absolutely terrified of going on the stage but you could write a script, well then you would just give it in and we’d cast it and give it to someone to do; so devising a script was the way of getting on the stage. And I was so keen to get on the stage, so I would devise! The best things that we did, Penny and I, we would write words to other songs and things, and then when they discovered what a gorgeous couple we were, ‘cos we were very glamorous and funny, and you know, and hilariously funny, and once we’d teamed up with Peter Burleigh, Rick Thorpe and Tony Green who were in our year, we became this group of five, who were like invincible, you know, and we just kept devising scripts all the time. The best thing about the Architecture Revue was collaboration! We had script writing nights where everyone just got so drunk in the end, I mean, we didn’t have drugs then, we had alcohol or beer and cigarettes. Script writing nights were just hilarious and you would get all these crazy ideas and honestly two heads were better than one in any situation, especially in writing.

The best thing about the Architecture Revue was collaboration! We had script writing nights where everyone just got so drunk

Was a lot [of content] pertaining to University experience?

The Architecture Revue was very political, was very, very clever. We were in the middle of the Revue, we’d done two performances, and the King Street Bridge fell down. They were building it at the time. Ah, I’m very old, aren’t I? The next night in the Revue, four boys got up in a barbershop quartet – Jamie Learmonth, Graeme Brady, Andrew Reed, and another and the boys sang [singing] “boom, boom, boom, boom, They said it was a heavyweight transport, transport, transport, They said it was a heavyweight transport, and the bridge came tumbling down, down, down, down!” and honestly, the roof came off the theatre, ‘cos it had happened that morning, you know, and they sang a song about it that night in the Revue. For me, this style of Revue, was like Beyond the Fringe, you know. It was utterly sharp, funny, clever and visionary, quite visionary. And, some years the Revue was bad, and in some years, it was brilliant.

It was very immediate always?

It was very immediate. People would come out of the woodwork who could play music, we had pianists and we had films in the Architecture Revue, and dancing and there always used to be a ballet in the Revue and then Tamara Winikoff came along and she did a few ballets and then she did her own solo ballets. There was a lot of competition in the Revue. And it got longer and bigger and bigger, sometimes there were 70 people in it.

Were people encouraged to become involved?

Oh god yeah, and as it went on it got harder and harder, as the pressure seemed to come on and the whole demographic would have changed after. I was just talking with Penny about this last night. We reckon we were at the last of the best times at the University in the sixties. We had total freedom, we were incredibly powerful.

This translated to theatre as well?

Translated to theatre, translated to our lives. We felt we were invincible, you know? We just did so much, and in the 70s, 80s and 90s, my son, Dylan Brady went through Architecture and he also directed the Revue and broke new ground with it but by that time he had a cast of twelve or something.

So when you directed it in 1966, tell me about your direction?

My direction….I had real vision, and this was the beginning, I think, of my capacity to visualise huge things, and it was very theatrical. I’d always envisioned the end of the show, ‘cos I’d heard Dame Clara Butt singing Land of Hope and Glory on the radio and it was hilarious — as I heard her singing it I just saw visions of battleships sinking and the whole British Empire going down the gurgler basically. There was a wonderful boy there, whose name I can’t remember, I’m terribly sorry – there’s a photo of him on the back of the album – I had him dressed up as Dame Clara Butt, but he was dressed up as Britannica with the horns- probably he was actually dressed up as the Valkyries I think! [laughter] He was draped in a Union Jack and he stood on this big ladder, and what I did was I just got everyone in the cast to come on for the finale. The finale used to just be an all-in-a-row: we’d all go forward, and we’d throw streamers, and we’d all go back. Well, I had the whole cast on stage and I remember the last [rehearsal], we were running out of time and I placed them all, and I brought all the ladders in and every bit of crappy equipment out onto the stage and they stood on ladders and boxes etc., but they all had to be absolutely deadpan and there was this gap in the middle which was the blank wall at the back and I’d got all super 8 footage of planes coming out of the sky and battleships sinking, old World War I films of stuff. It was hilarious. And that film got shown and everybody stood and they all had a British flag and we all sang Land of Hope and Glory. And that was the finale; we all just stood there and people all threw streamers in at us and we didn’t move and it was just hilarious. I had a lot of ideas for scripts. I had a row of tap dancing chorus nuns, because at the time I remember there was a theme on the radio called [singing] “It’s a great life but it can be greater, why try going it alone, the blessings you lose may be your own” and it was an ad for the Church — I don’t know which church, so I had a row of nuns and some of them were guys. It was 1966; I don’t think guys dressed up as nuns then.

There was no other cross dressing going on?

No, not then. They didn’t dare be nuns. It was pretty outrageous.

So did you have a lot of resources for the actors then?

We did. We were very clever, we sort of had to rely on Bill Mitchell, who is now a Professor in America; he’s just brilliant. He designed the set for that Revue, and he designed an egg carton set. We were in the Prince Phillip Theatre, the first year we did it in there, and the place was shocking sound-wise. It was a concrete shell, it was just really bad, so Bill just created egg carton sort of sound baffles and it was a beautiful thing. It was really fantastic what he did. The resources would come. People had fathers who were builders and who were in the trades, you know, a lot of people had fathers who owned timber yards and you’d go out there and I think that’s where I really learned to beg, borrow, steal whatever I could for my theatre. I’ve always done ‘poor theatre’ for some reason. When I say ‘poor theatre’ I mean theatre that doesn’t have many resources, and I’ve always learned to think on my feet and to create theatre out of nothing, to create it out of one piece of cloth, you just cut it right back to minimal stuff. I don’t know what happened to some of those people who learnt about stage life and went onto theatre maybe, Peter Harkin, I remember him, he was a savage stage manager; Peter Rowe; they were all fantastic.

I think that’s where I really learned to beg, borrow, steal whatever I could for my theatre.

What about costumes?

Well, we had people who made costumes. All the women got involved. Eva Collin. They would just take over a room in the basement of some building and you’d go down there and they’d have all these sewing machines in there and we’d go to Job Warehouse in Bourke St. and we’d get all our materials. You know ‘Rose’?, no not ‘Rose Chong’, she was at the Pram Factory, but we had people like Rose Chong. We abounded in talent. I don’t think that happens now. I mean in Dylan’s Revue they just wore white tee shirts and white pants or something.

And yours was quite elaborate?

Oh we had wonderful stuff.

And apart from the year it was in the Union Theatre, where else did you stage..?

The Union Theatre. Every year it was in the Union Theatre. I’ll never forget it. We’d go into the Union Theatre and I used to love the smell in the back of the Union Theatre. That smell of old stage paint and that musty, sort of echo-ey, damp-ish sort of smell in there, it used to excite me to my very bones. The dressing rooms in the Union Theatre were so tiny and you can imagine a cast of 70 cramming in and some people only had one thing to do, and they’d be in the dressing room all night! [laughter] And we’d all be there doing our makeup and I can remember doing Joan Sutherland in one Revue. She’d just done ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ out here with all the blood and we did a spoof on Joan Sutherland. And I can remember getting in and doing this big, square jaw makeup and this wonderful hair, and I looked so like her. It was awful! [laughter] The blood stained nightdress.

I used to love the smell in the back of the Union Theatre. That smell of old stage paint and that musty, sort of echo-ey, damp-ish sort of smell in there, it used to excite me to my very bones.

And how did the audience respond?

They just loved it. They were sucked in though, you know, you couldn’t disappoint them.

Were they all students?

There was sort of an ancestral echelon of Architecture support [that] would always come to the Revue. You’d go there and you’d always see all the old people who’d been in the Revues – they’d all be there. It had a reputation like ‘Beyond the Fringe’. It had a reputation and you just waited to go to see it. It was incredible and I mean the whole University would come.

So it was a pretty important day in the theatre calendar?

You couldn’t get tickets. It would be booked out and you just had to get the tickets or you just didn’t get to see it.

How long did you put them on for?

Oh it was only on for a week or something. We always said it could have run for three or four weeks. The whole thing was that you’d be hyped right up to it and you’d do it, and then you’d go back to schoolwork because you’d missed out a lot on lectures and submissions. But they always used to give us design extensions and apparently this year Peter McIntyre just stopped all extensions on design and killed it. Apparently this year a group of Architecture students did a Revue in a pub, which just about says it all, doesn’t it?

So how long did it take you to prepare each one?

The Revue? You’d start working at the beginning of the term. You’d have a few meetings at the beginning of term and you’d get up excitement, and you’d have a barbecue and you’d have something else. I always remember Simon Reed at a barbecue – no, maybe that was a First Year barbecue, yes – when he put his penis in a hot dog roll and went round and offered it to the young freshers. A charming man! [laughter]. You’d have a barbecue, and then of course the Revue party at the end of the Revue was just legendary, and it had to be in a secret place because the whole world would have gone. Usually it was held out at the Jelbart’s place at Eltham which was miles away- it took hours to get to Eltham! Right up the Heidelberg Road, uphill along a dirt track out to Eltham. In those days that would go on all night and people would just, oh look, it would just…And there was always enough money and people would buy kegs and kegs and kegs of beer, there were barbecue sausages and they never ran out of alcohol at a Revue party!

the Revue party at the end of the Revue was just legendary, and it had to be in a secret place because the whole world would have gone.

Did you need to promote the idea of the Revue at all, did you do any promotion?

We did posters, every year there was a competition for the poster and the poster would be chosen. And every year they made a record. There is a recording of every Revue with selected items.

Where are they?

I have a few. Penny has a few. Clive Fredman is your best source of getting any Revue memorabilia because he really does have a lot. Peter Jones has the movies. I would guarantee that the Architecture Faculty has got nothing.

Tell me about the other theatre you were involved in at Melbourne Uni?

OK. Well for me, as I’ve said, the first year I just did the Architecture Revue, but then I would go out and there was a lot of stuff, the MTC were performing at Melbourne University and at Russell Street. There was only the Union Theatre and they had Russell Street Theatre. I can remember seeing certain shows at the Union Theatre. I remember seeing ‘School For Scandal’ which had Max Gillies in it and I remember Bill Walker was in it. I remember seeing ‘Ubu Roi’ which had Bill in it again. Who directed that? It was an extraordinary production. It was my first ‘Theatre of the Absurd’. I saw a very funny ‘Hamlet’ at the Union Theatre with Kevin Colson playing Hamlet and I happened to go in and see it when there was a whole lot of school students in there. It was the funniest thing because at one point he said “oh let go of me or I’ll make a ghost of him who stops me” with his sword out, and unbeknownst to himself he had stepped back into the set and he had bent the scabbard of his sword, right, and he’s desperately sheathing his sword and of course he could only get it in so far, and he can’t work out why it’s not going in and he refuses to look at it, because he’s such a bad actor, you know, if you know it’s not going in you look to see why it’s not going in [laughter], so he pretended it was going in – that’s great acting isn’t it? Anyway, subsequently the audience was shrieking and pissing themselves laughing, these kids, and I remember he got so angry, he stopped and told them to ‘fuck off’, it was terrible!

Was the standard usually above that, I mean this sounds quite amateur-ish?

[sigh] Well I suppose you wouldn’t call it amateur-ish. I think he just spat the dummy that day. But then there were students here like Patrick McCaughey. Patrick did a lot of student theatre productions that were extraordinary. So did David Kendall. These two men in the sixties ruled the theatre.

And were you in any of them?

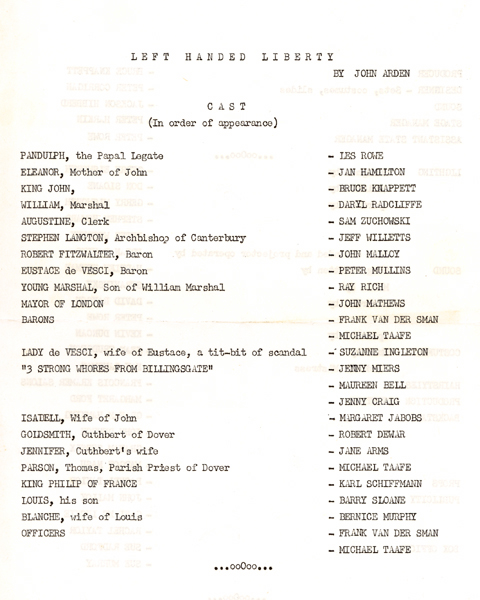

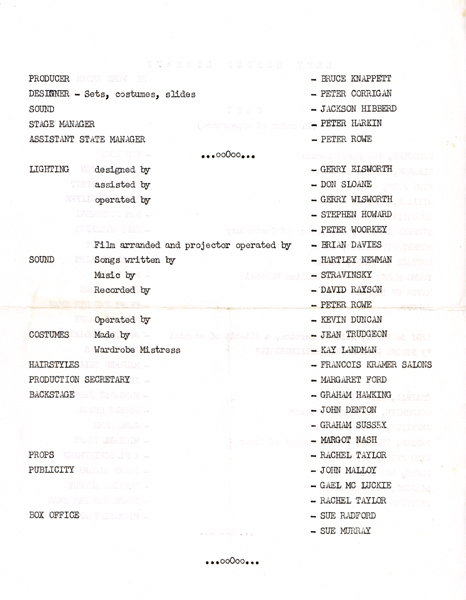

Yes, I was in some of them. I was in a play called ‘Left Handed Liberty’, by John Arden and ‘Bluey’ Bruce Knappett directed that and was also in it, playing King John, and I had a strange part in that where I had to sit on the stage and say absolutely nothing. It was interesting.

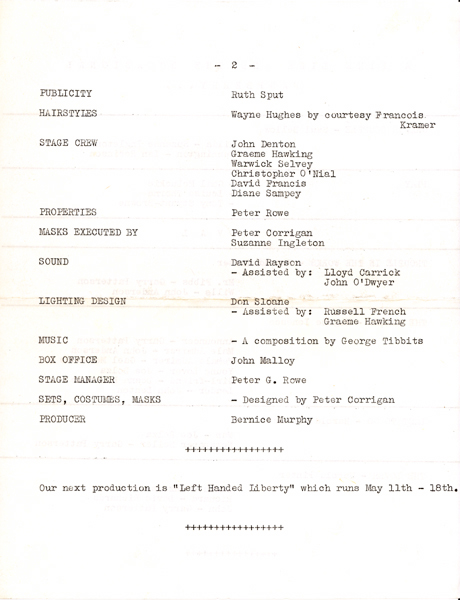

Peter Corrigan designed all the sets during those times. He would have a great archival resource for you I’m sure. Peter would have kept copies of everything he did. Patrick did ‘Hamlet’ in a tent. They pitched the tent outside the Union building. That was an extraordinary production. Peter Curtin played Hamlet, Graeme Blundell played Polonius, Kerry Dwyer played Gertrude, Barry Sloan played Osric, Richard Brown who was in that Revue played Horatio and Peter Corrigan designed it and I made the costumes for that with a woman called Gayle Allen who now lives in Italy, and Joanne O’Rourke in 177 Grattan Street. We sat in this tiny little terrace house upstairs in this room and we sewed. I sewed my finger into a piece of leather that day, I’ll never forget it. Corrigan had designed these incredible costumes and I was making Hamlet’s jacket. It was black leather with black velvet, all in layers, it was incredible. Now where did they get the money for that? I don’t know. Corrigan was amazing at making costumes, you know, he just flinched at nothing, and his posters were extraordinary.

I saw Pinter’s, ‘The Birthday Party’ which he designed, which had Jon Dawson in it, and Graeme Blundell was in it, and Kerry and possibly David Kendall directed that. I saw David Kendall’s direction of ‘A Man For All Seasons’ in the Chapel at Trinity College with Gus Worby playing the main narrator role. That was just amazing, in the Chapel, it was the first time I’d seen theatre in a church and it was just extraordinary. And the plays that I did at University, I did ‘The Boyfriend’, I played Maisie and that had the Warden, Mick Sinclair- Wilson in it and it had Ron Field’s, (who was the Union Manager,) wife, Margaret Field, a light opera singer and she played the main role and I can’t remember who else was in it. Where I’m living now, up in the country this woman said that she had worked on The Boyfriend, and I said ‘I was in The Boyfriend, what were you doing?’ and she was working backstage, and I was just amazed. Anyway, for that role I won the Murray Sutherland Award which was the theatre award that they gave to an undergraduate student each year. At the presentation of that award, Joyce Grenfell was in town doing a show and Joyce Grenfell presented that award. I can remember lunching with Joyce Grenfell and when I met her she talked to me, she was so wonderful, oh god she was funny, what a wonderful women. She said to me ‘Suzanne, if you make them laugh, [that’s] a very, very wonderful thing’. I think I can make them laugh, and subsequently went on to do that.

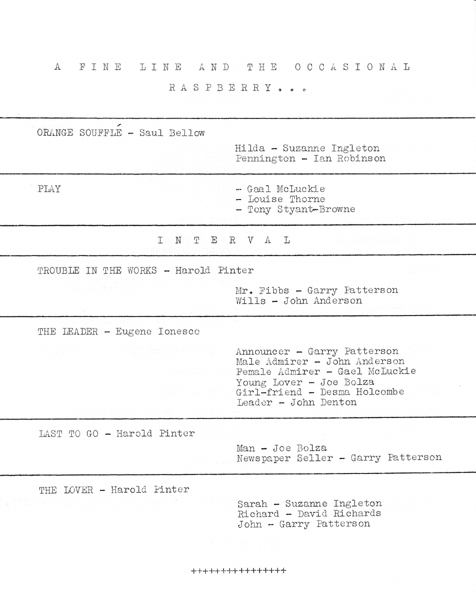

The other student theatre that I did, I just can’t remember but that year I’d finished but I came back in 1967 to do a Bernice Murphy production- she was putting on a play collection called ‘A Fine Line and The Occasional Raspberry’ and I was doing the Saul Bellow ‘Orange Souffle’ and also ‘The Lover’ by Pinter. ‘Orange Soufflé’ was with Ian Robinson and I really had no idea what I was doing. Again Corrigan designed the set . Even when I did Hibberd’s ‘White with Wire Wheels’ I had no idea what I was doing. I mean I wasn’t an actor’s arsehole really. I got by on the seat of my pants by just doing my ‘schtick’ I suppose you’d call it.

Did you used to get some sort of training?

No. Nothing. You just got out and did it which is very much like working at The Pram Factory. You just got out and you did your thing. Which wasn’t good enough for me and for the rest of us at the Pram either, you know, the group I ended up working with, we just had to go do training, I wasn’t trained.

I mean you’ve mentioned directors, Patrick McCaughey and David Kendall. Did they offer you any sort of acting guidance?

Oh, not so much acting guidance because in a strange way they really stood back a bit, because I suppose they could see that you had some sort of quality and a passion and something was working. They would encourage stuff and my voice wasn’t trained and I’m sure that half the stuff, you know, no one ever heard it! [laughing]

But they must have in The Boyfriend?

‘The Boyfriend’ was great fun. My passion was always to do musical comedy. I never quite got to the musical comedy. I’d love to do ‘Gypsy’ you know, that would be like a feather in my theatrical cap if I could go and do Gypsy, that would be just fantastic. But I sort of missed the boat on musical comedy. But just to go back to the ‘Fine Line and The Occasional Raspberry’ There were three acts in Pinter’s play The Lover.. And one night I went from Act 1 to Act 3 and I had to start the beginning and I completely missed out the second act and I didn’t even know it had happened! [laughter] until the curtain came down and the poor guy who was working with me turned around to me and he screamed “What the fuck were you doing!” and I went “What, what? That was great? What?” “You missed out the second act!” and I can remember at one point turning around and brushing my hair because the second act and the third act sort of open the same way with her doing something and he had his back to the audience and I can remember him going [gesticulates] [laughter] and I can remember thinking “What is wrong with him?!” [laughter] Oh my god, so, but you can see where I was at, I mean I had no idea what I was doing. I can remember in the middle of Orange Soufflé, running out one night. Ian Robinson is sitting in this sand pit in the middle of the stage that Corrigan had designed for him, and he is sitting in the sand pit in the middle of the stage doing this thing with his buckets or something, he is an old roué, I’m a prostitute and he comes to me every year and this final year she cooks him an orange soufflé, hoping it will rise and hoping he will marry her, and Ian’s trying to do this Jewish New York accent! [laughter] I can remember going offstage to make the soufflé and panicking, I couldn’t remember my lines, and hissing hysterically at Peter Rowe, the stage manager of the show ‘what are my lines?!’ He didn’t have a clue and he said “I’m the fucking stage manager!” and I went blank… blank, and thankfully that never happened again.

I can remember going offstage to make the soufflé and panicking, I couldn’t remember my lines, and hissing hysterically at Peter Rowe, the stage manager of the show ‘what are my lines?!’

Did you ever have anyone give a cue?

I’ve never had to do that but there’s a very funny… Oh, can I tell you a very funny story? The funniest cue story that I can tell you was that I was in New Zealand watching this divine man, Danny Boone, who should have a film made about his life and he’s passed on now. He lived in New Zealand and he at the age of eighty, had started an acting school, so he had all these students and they had a presentation night. There’s all his students up there doing their thing and I went along to see it because I was performing one of my shows in New Zealand. One little medieval scene, there was this young girl and a young, dark haired – maybe a Maori – boy, he was very handsome and he had broken into her apartment and she was this sort of lady and he’d climbed in her window and they obviously were meant to have a conversation. He said something to her and then there was this terrible frozen silence, a silence where there was absolutely nothing happening and she’s looking at him and he’s looking at her and you’re thinking who’s forgotten their lines and you couldn’t tell because you were just so utterly transfixed in horror for them and you could hear this voice whispering off stage to them. Finally she heard her line and she turned around almost catatonic and raises her hand and says, ‘Silence!’ [laughter] That was the line she’d forgotten and the silence had gone on for two minutes which is a long time. I just pissed myself and I couldn’t stop laughing then. Terrible of me.

But being at the University, the MTC they were in the Union Theatre, that was their theatre. I sort of got in on the edge a bit with some of them and I went to all the MTC shows because I think I just yearned to be up there in real theatre, you know. And I can remember Malcolm Robertson saying to me, and this was at a point when I was about to go to England to go to the Central School of Speech and Drama, ‘Why don’t you come to the MTC, I’ll get you in there,’ but by then I had a total cultural cringe thing with Australia and I said “no, I’m going to England, I’m going to go where the real theatre is”, because that’s really what was subliminally taught to us, you know. And I remember talking to Blundell not long before I was going to go and I said ‘oh I’m going to England, I can’t stand it here’ and he said ‘No, I’m going to stay here, it’s going to be great’ and he had joined the MTC by then, carrying spear mostly. And so I went to England and failed the entrance audition to the Central School of Speech and Drama, and on the rebound off that I got married, which was a very silly thing to do but it was an excuse. If I hadn’t got married then I would have had to make some sort of foray and join rep theatre and gone off and tried to do that, you know. I was so ashamed, I was so ashamed. Because I’d had this huge fanfare when I left, you know.

by then I had a total cultural cringe thing with Australia and I said “no, I’m going to England, I’m going to go where the real theatre is”

You had had some success at Melbourne Uni?

Yeah, I’d had some success but look, on the other hand, you know, thank god for my destiny because had I gone to the Central School of Speech and Drama I would not have done what I have done, you know? I’ve always been well protected on my pathway, it is, it’s fantastic. So when I came back to Australia there they all were at The Pram Factory. That’s it and we went on from there.

At the time you were at Melbourne University and you didn’t have any training, were you influenced by any theories of theatre or was anything sort of popular, or…?

I read nothing. I never read the American TDR, I never knew about the Tulane Drama Revue, which was the bible at the time when The Pram Factory was happening. My mother always took me to theatre, for which I thank her. She always took me to all the musicals, even to opera and but I loved going to musicals. And she never failed me by taking me to them, and we’d always have the best seats, so I was always at the front and I could see their faces, you know, and all that sort of stuff. I just loved the theatre, it was my passion. For many years I killed it, I put the flame out you know, but luckily I came back to it.

I just loved the theatre, it was my passion. For many years I killed it, I put the flame out you know, but luckily I came back to it.

You mentioned that you saw an extraordinary production of an absurd piece?

Oh, Ubu Roi, by Alfred Jarry

That was showing something different from the general mainstream theatre that you were […]

Yes, and you know what they did, and you can check this out but at Melbourne University, onetime, they did a ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ Festival and I think they did ‘Rhinoceros’ and I think they did ‘The Chairs’. I remember seeing, yes I did see The Chairs, because I remember who was in it. And I saw Krapp’s Last Tape which Bluey Knappet did. He was extraordinary.

Why?

Oh, because he was extraordinary. He was magic. In the Union Theatre.

Tell me about the production

Oh, it was just so simple. The piece is not a long show. It’s by Samuel Beckett and the man sits with tape recorder on the table and he plays the tape recorder and his memories are on the tape recorder of when he was younger and then he remembers and then he speaks again and he is reliving his memories. His mother’s died but Bluey never, I don’t think he even stood up, he just sat there the whole time and even though he was young he could look 50, 60, 70, he was just wonderful and his voice could be a low growl and you could hear every word, you know.

And I remember the first night I met David Kendall which was another extraordinary meeting too. He was a friend of Tamara Winikoff’s and we were in the middle of teching the Architect’s Revue at the Union Theatre and that was always like a nightmare. Nothing in theatre could ever disturb or shock me after having years of Architecture Revue techs where we would go to six in the morning. There were no Union laws, no rules, nothing, you just went on until you finished the fucking thing, which was like, sometimes there were 120 acts, you know, it just went on and on and on. Anyway, I can remember everyone would be sitting with their feet up like this and there’d be sort of old pie trays and everything around and people would be lying under blankets and they’d hear their name called and they’d sort of stagger down at four in the morning – they’d been there since eight o’clock the night before waiting for their act to come on! [laughter] It was just terrible! And I can remember coming up the back of the theatre and there was this cool looking guy sitting there. He had these glasses on and this black leather jacket and he was sitting with Tamara and I’m sure he was putting on this American accent and he was very sexy and I thought what an interesting guy, you know, he’s all in black and all that stuff, and that night, I had a little car because my Dad had bought me a little Mini-Minor with the number plate ‘Hot 337’ which was an embarrassment! [laughter] and I drove him home to wherever he lived, I can’t remember where it was, and we went into his flat and he played these records to me that night. We didn’t have sex, didn’t even kiss or anything. He just played these records of train noises to me until about 5 o’clock in the morning! [laughter] I thought it was fabulous! [more laughter] I was easily swayed, play me a train whistle and I’m yours! And David Kendall subsequently left the Uni.

Nothing in theatre could ever disturb or shock me after having years of Architecture Revue techs where we would go to six in the morning.

Why was he so important?

Because he just revolutionised theatre, he brought it up to standard. He created pieces of theatre that your jaw would hit the floor today to see what he did. And all those directors, so lucky to be working with designers like Corrigan and actors like Jon Dawson, Kerry Dwyer, Graeme Blundell and Max Gillies. We had the cream of the crop then. It was an extraordinary time. It was a time out of time. I don’t think there were any actors working at Melbourne University now that could come out and do what those people did. I don’t think they are there. I don’t know, maybe they are.

So was he just experimenting?

Oh yeah, and also Patrick McCaughey too but he chose to go on to the path of art criticism because James McCaughey had sort of taken over the theatre role a bit, so he said “well you’re going to do theatre, so I’ll go and do art”. To me, there was room enough for both of those brothers in the theatre world. I think Patrick was extraordinary, he was utterly unique, he had a way to draw from you the essence of what you wanted to give to a piece. His utterly extraordinary intelligence around a script, or ideas to be found in script, and the Shakespeare stuff he did, I wish I could remember the other things. But he was just always doing stuff and David the same, and their envisioning of theatre, you know, and their creation of it, the set for The Birthday Party. You should have seen it, it was like a sail and it was all covered with newspaper and it was all sprayed a dirty yellow with navy blue and white polka dots everywhere. In a way we took it for granted because in a way we were creating such new theatre. Nothing like this was happening at MTC. MTC, you know, had doors that opened and drawing rooms and real windows and bookshelves with books on them and you’d go to the MTC and you’d just be like – bored. And you’d go up to the Union Theatre and you’d see this stuff that student theatre was doing there or in the church or in a tent, I mean McCaughey’s Hamlet in a tent – it was fantastic!

Obviously there was a lot of receptiveness to that as well?

I also think it was what we expected. There were no standards for us. So we just had to do something better and better and better. At the same time I do remember, this is a bit later, because I remember I was pregnant when I saw Rex Crampthorne, who came down from Sydney to do The Tempest. They did it in the Guild Theatre and they didn’t have any set and I remember that just blew me away to see that.

Why was that?

Oh, Gillian Jones was in it, David Cameron he played Caliban and he also doubled playing Miranda’s lover. They sort of sang it, it’s in verse but they changed it, it was like you were listening to fairies singing something, you know. I think the more of that experience that Greek actor who was married to Maggie Cameron, arrrgh my brain! Anyway, you can look it up. I can see him so clearly. In Death in Brunswick he played the guy they killed. The Greek guy. Nick Lathouris. He played Prospero, he was just incredible! The whole thing was like something I’d never experienced and I’d just spent two years in London seeing theatre all the time. The theatre experience should always be incredible. The people who were in The Pram Factory were the people who had been in that theatre. Graeme Blundell, Max Gillies, Kerry Dwyer, that was our training ground, that was our seeding ground. David Kendall teamed up with Peter King I think. Peter King did a production of Richard the Third, I think, with mad Margaret played by Kate Legge and they did it. David just let Peter King have it in the end, because he could see that he should just run with these ideas that he had. And this was pretty radical. He doesn’t put the audience in the theatre of the Union theatre. He lifts up the fire curtain, he lifts up the back curtain and he performs the whole play in the paint shop of the Union Theatre and the audience walked around and we were told to stand here or there and subsequently when Lindsay Smith did Brecht’s The Mother we had a moving audience. It was fantastic, it was radical, you know. Peter King played Richard The Third, he directed it and he was in it.

Exactly, rather than being competitive between you, you were just encouraging each other in a collaborative spirit towards producing….

Oh I think collaboration is a very true word for it you know, and stars did rise you know, but they deserved it and they had the ideas and why not?

Did you do any College theatre at all?

I wasn’t in a College. That’s just reminded me that ‘The Man For All Seasons’ was the Trinity College play. I directed a student theatre production of ‘The Dragon’ which was a bit weird.

When was that?

It was around ‘75 and that was in the Union Theatre.

What sort of production was it?

It was a student theatre production. The poster is still at the top of the archway in Tiamos. I think I can see it up there – The Dragon.

Were you happy to do it?

Oh, it was just fun. I put my hand up and said I’d go in and do it and I hadn’t directed anything before that. It was interesting in that I did it very quickly and only after I’d finished it, did I realised what the play was about! [laughter] The girl I chose to be the heroine of the play – there was this wonderful girl in there who had this wonderful quality who was quite plump and a little overweight and she was absolutely fantastic. The girl who thought she was going to get the lead, who was the body beautiful, but was without a mind – not without a mind but she was just boring – and this other girl was so brave and wonderful and after I cast her in the lead she came up to me and said ‘I’ve never been cast like this before, it’s never happened to me’ and I thought it’s just because of her body and she’s just a bit overweight. She was just wonderful.

And when you were at the Union Theatre did you get involved in any other activities outside of just the plays – meetings or workshops?

I can’t even remember meetings. I think I heard about ‘The Boyfriend’ happening and I was asked to do ‘Left Handed Liberty and there’s something in the back of my mind but I can’t think of what it is now. Oh I remember! Ron Falk, Ron Falk was in there and Sue Neville. You know they did the Dark Side of the Moon, the Dark of the Moon, one of those plays, and I remember going to see that and coming and helping her but I didn’t have time to do it. We were very insulated at the Archi school. You didn’t really hear much about what was going on. For me going out to do ‘The Boyfriend’ was a real excursion out, and even though I just loved it I knew my work was going to suffer because of it, you know.

And with the non-Archi Revue?

Janice Hayes is another name that comes to mind. Janice Hayes did a lot of wonderful student theatre.

Was there a lot of support available for non-Archi Revue theatre?

In the Uni? Well I think Melbourne Uni Student Theatre got a grant to do their productions. The Architecture [Revue], we got some sort of grant out of the student funds. I don’t know how the Union Theatre group went or whether they made money out of the productions. Some productions were well received, you know. And then there was the University Revue, which I did a couple of. I can remember one Revue with Julian Pringle and I think David Kendall might have directed that Revue and I know that Tony mcNicol directed one with Patrick. I think I did a couple of Revues and they were done on a shoestring and rehearsals were like, you know, you’d meet at 5 o’clock and do half an hour and then you’d have to go and you’d meet again. You know, it was very incohesive, but we were old hands at it, and they did select a group of people who would do stuff and muck in and get it on. We used to get scripts from everywhere. I can remember we did all these scripts from This Was The Week That Was a British show. I can remember that somebody came in with a book of scripts from This Was The Week That Was and we just did that! We ripped off the British icon, David Frost, we did a lot of that stuff. We just stole it and did it. But on the other hand we also wrote some scripts and stuff. I just remember being given something and I don’t remember creating much when I left. All the Archi Revue stuff was really original. It was quite extraordinary.

Tell me about the theatre reviews you got. Who reviewed the shows?

Well you would be reviewed in the university newspaper, Farrago, and the thing that happened with ‘White With Wire Wheels’ which was the first breakthrough was that it was a student production, David Kendall directed it, so it must have been a student theatre production. I’m not sure about that, have a look at that, Patrick got to see it and we also did that in the Architecture Theatre, which is the year after I’d directed the Revue in ‘67. And after he’d seen it he said ‘my god this is good, this is so incredible, this is the beginning’. Because in that play the language, the vernacular was being used, the whole concept of the play just tapped straight into the ‘now’ language of the youth and the people all around and it was incredible, and he went away and because of that, he [Patrick] who was writing art reviews for The Age, wrote a theatre review of it and it got published in The Age and that was like the first time a student production received a review in a major newspaper. I don’t think it happened for a while again after.

And did the people who reviewed for Farrago respond to the Archi Revues?

Oh, they loved them and I remember Peter Corrigan wrote a review one year under the pseudonym of Peter Van Brugh [laughter] and there was a photo of me in the middle of it with the caption ‘Sue Ingleton showing off talent’ [laughter].dressed as a playboy bunny of course!

Would you say there were any trends either in the types of plays that were chosen or in the style of production?

The types of plays that were chosen were very much like the new, the English playwrights and the new American wave like Edward Albee and so on. I saw Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf at the Union Theatre I think with Bunny Brook. The student theatre sometimes did theatrical seasons too. I can remember the Theatre of the Absurd being a distinct theatre season, a festival. And then you’d do theatre like The Boyfriend. It was fairly eclectic. There was never an original play and there was never a group devised play. You know, there was never anything that came out of us as it were. No one ever set up a project in Melbourne student theatre where you would create a theatre show or a play or a performance. It always was, someone had a passion to do a play and then they would try and get it up. It’s interesting, I don’t know how they got the money. There must have been a budget. No one ever got paid anything so you just had to basically scrape together your props and things. Everyone worked for nothing and I guess the theatre was ours so we didn’t have to pay rent on the theatre or anything.

Just tell me how your student theatre experience has really impacted on your later career?

I think, in terms of impact on my later career, I think, if I hadn’t have done it I think just part of me would have died if I hadn’t been able to go on to the stage at Melbourne Uni. I mean to touch base with that every now and then was what kept me alive, because Architecture wasn’t really keeping me alive. I mean, being a student at Melbourne University was fantastic. It was an extraordinary, outrageous period of my life. It was just wonderful and I had the best time, you know. But when it came to going into theatre as a professional and starting in The Pram Factory with a whole bag of tricks that I had, the real change for me was to actually forget everything that I’d ever done, you know. I had to let it go. I had to shed layers and layers, to peel back all those little tricks and things that you’d hide behind. To develop a true voice for theatre and to understand how, you know, I mean I think I was always very intelligent around theatre but to also really go deeper and deeper. There was always another layer to find in something. You were never quite there, you know, so there was always a challenge no matter what you had done with a scene. You always knew that if you had done it one more time you would have just gone into another layer with it, so I had to learn that. I had to re-learn everything.

It was at the right level for me because I also managed to do my degree at the same time. So you can see how much I was split in half and really dancing along the surface of it, really, in student theatre. There must have been something happening, you know, because you got a lot of feedback from it, instant sort of feedback, but always inside me there was this [laughter] secret little doorway that if I opened it said ‘Fake!’, you know [laughter]. It just felt like I hadn’t, like I was just pretending, you know. Whereas now when I do something, I’m right inside all the doorways, I’m in the middle, and it’s just so different. It’s just such a different experience for me now. It’s so true and exciting and completely unknown.

It sort of was then as well?

Oh yes, but it was more lovely, lovely, you know [laughter]. I think it’s extraordinary at the time with all those people there that we never once thought to run a workshop, you know. I’m thinking about it now and knowing …

But you were busy doing shows?

Well, busy doing shows, but even so, we didn’t think about theatre like that then. You know? We weren’t into training. We were just into Performing!

But at the same time you were doing quite radical things in the theatre?

Yeah, maybe because there were no rules, you know. There really were no rules. One reason that I… I could have gone on. Instead of doing architecture I could have left that and gone to NIDA because NIDA was really the only place where it was happening. But I sort of didn’t feel confident enough to leave Melbourne and go and live in Sydney.

Look, I’ll just hang this up for the camera. This was a University Revue I think directed by Robert Thorpe. I’ve never heard of him, I can’t remember him at all. Isn’t that amazing. So there we all were. Can I put it down now? D.K. Williamson, don’t know who that is, Stephen Cook who used to do a comic strip in Farrago who committed suicide, Graeme Brady who I later married, Jackson Hibberd, David Kendall, Suzanne Ingleton, Phillip Adams.

END OF RECORDING